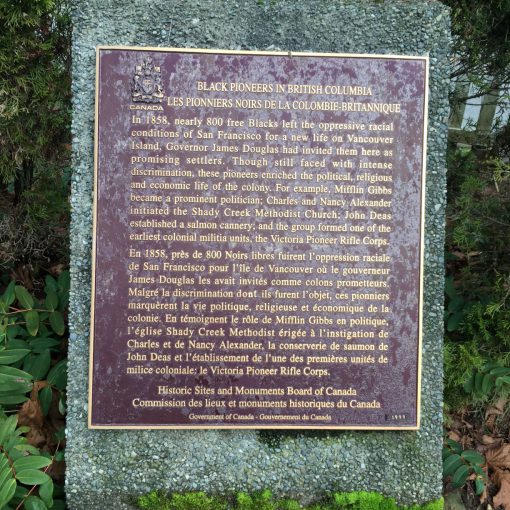

April 25th,1858 the Steamship Commodore sailed into Victoria harbour from San Francisco. On board were 35 Black people, the Pioneer Committee, to meet with Governor Douglas. They were free men and women seeking a place where they could raise their families, educate their children, practise their professions, enjoy the results of their hard work, vote, live without fear and live with equality under the law.

This plaque was installed on August 18, 1978. The plaque states “In commemoration of the arrival in 1858 of the first group of Black settlers to the Colony of Vancouver’s Island.”

This plaque was installed on August 18, 1978. The plaque states “In commemoration of the arrival in 1858 of the first group of Black settlers to the Colony of Vancouver’s Island.”

It is part of “The Parade of Ships” installation by the City of Victoria. “The Parade of Ships” is a series of bronze plaques that line the Upper Causeway overlooking the Inner Harbour commemorating historic Victoria harbour events.

The arrival of these settlers begins with this Pioneer Committee, formed by the Black community in San Francisco. This community was well organized for some time, holding regular meetings at the First African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (established in 1852); and some attended THE CONVENTIONS OF COLORED CITIZENS OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA (1855-1865). These California conventions were an off-shoot of the National Colored Conventions and “were a response to blacks being treated as second-class citizens and constantly threatened and violently assaulted by white men without legal and political recourse in Gold Rush era California. The first convention in 1855 marked the beginning of organized civil rights activism in the American West.” [1]

Two landmark cases in the U.S. were instrumental in their decisions on emigrating.

The Dred Scott Decision in March 1857 when the U.S. courts decided that no Black person, free or enslaved could claim U.S. citizenship. If you are not a citizen then:

- You could own property and run a business as long as you paid the taxes but you could not vote.

- You could not testify in court against whites; if you were robbed or assaulted by a white person you had no recourse through the court system.

- Public institutions or services for Blacks were segregated or non-existent.

The case of Fugitive Slave Archy Lee. Archy Lee was born into slavery in Mississippi in 1840. Lee’s slave-owner, Charles Stovall, brought Lee with him to Sacramento, California on October 2, 1857. While in California, Stovall rented out Lee for his wages. In January 1858, when Stovall decided to return to Mississippi, Lee, age 18, escaped from Stovall. Archy Lee was arrested, freed, and then arrested again as various attorneys, and state and federal lawmakers rendered and defended their decisions based on ambiguous and disparate slave laws, property laws and state laws. On April 14, 1858, a final trial in California held that since Lee was in California, a free state, when he escaped and had crossed no state lines to escape, Lee was declared a free man.

On the evening of April 14,1858 at the Zion Church, the Black community were celebrating Lee’s release, as they had helped fund Lee’s legal defence. In the midst of these celebrations Jeremiah Nagle [2], captain of the steamship Commodore which sailed regularly between San Francisco and Victoria, arrived at the meeting. It is said that Nagle came well-prepared to the meeting with maps of Vancouver Island and a letter from “a gentleman in the service of the Hudson’s Bay Company of undoubted veracity” [3] giving details about the colony and welcoming the Blacks. The letter has not survived but it is understood that because of the implications of the information provided by Nagle, most historians agree the invitation could only have come from Governor James Douglas.

“On April 19th another meeting was held to form a Pioneer Committee of sixty-five who were to embark the next day on the Commodore for Victoria. Only thirty-five were able to make the sailing in time. The next day they were seen off by almost the entire Black community at the wharves.”[3]. They arrived in Victoria on April 25th. [4]

The delegation of three that met with Douglas included Fortune Richard, Wellington Delaney Moses and Mr. Mercier. Mercier returned to San Francisco reporting “Governor Douglas had made them feel welcome, and the delegates’ meeting with him had been very cheerful and agreeable.”[3]

Based on the meeting with Jeremiah Nagle and their meeting with Douglas; they understood they could:

- Purchase land in the colony at a rate of $5.00 per acre; which was considered an exorbitant price; and

- After nine months residence any landholder had the right to vote in municipal elections and to sit on juries; and

- Have the right to all the protection of the law; and

- To become British subjects, however, they needed to reside here for seven years and take an oath of allegiance.

Wellington Moses wrote “To describe the beauty of the country my pen cannot do it. It is one of the most beautifully level towns I was ever in … I consider Victoria to be one of the garden spots of the world … The climate is most beautiful..”[3] Richard and Moses stayed on as did many others “who lost no time in getting settled. Many bought land in town. Some formed a brick-making company, and others found work at once on the farms of white settlers who were delighted to hire them” [3].

After these meetings and over the next many months Blacks began settling in the Colony of Vancouver Island including Archy Lee.[5] Most were born in what were known in 1858 as Slave States: District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, and Virginia; and Free States: California, Illinois, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania. They had travelled or moved to California previously; others specifically travelled to California when they heard about Douglas’s offer. Others came from the Caribbean: Jamaica, Puerto Rico, Barbados, Bahamas; and other parts of Canada. There were no mass migrations as happened on the east coast. Families, relatives, and friends travelled together; and some were single emigrating on their own.

In 1997 the Government of Canada recognized the migration of these Black settlers as an Event of National Historic Significance.

In December 2020, the Community Story “BC’s Black Pioneers: Their Industry and Character Influenced the Vision of Canada” designed and developed by our Society, opened at Digital Museums Canada.

In August 2021 “Hope Meets Action: Echoes Through the Black Continuum” opened at the Royal BC Museum. “Against the backdrop of white-centring walls, this exhibit daylights the living and ongoing history of Black belonging, told in this manner by the Black community for the first time”.

In November 2025 “1858:Black Routes, Black Roots” opens at the Maritime Museum of BC, Victoria. This exhibit takes us through their journey via the steamship Commodore to arrive here, in 1858, as the first group of Black immigrants to Vancouver Island. We follow not only the story of the Pioneer Committee, but the history of the many early Black immigrants that came after (via various routes and steamships). The story does not end upon their arrival, but rather continues through their legacy – their contributions to local society, their social, economic and political impact, and their legacy through family and descendants.

Notes:

[1]Ruffin II, H. (2009, February 04). The Conventions of Colored Citizens of the State of California (1855-1865). BlackPast.org. National Colored Conventions

[2]Jeremiah Nagle was born in Ireland. His principal occupation was as a seafarer, establishing himself as a master/captain early on. He commanded ships in England’s merchant service to Australia and New Zealand in the early days of the settlement of those colonies, and was one of the pioneer residents of both New South Wales and New Zealand. He was back in England and from there he sailed to this western coast and after a few years in California he came to Vancouver Island. It is speculated that because Nagle lived in California, he would have been well aware of the situation for the Blacks and that Douglas and Nagle were well acquainted. In March 1859 James Douglas appointed Nagle to act as Harbour Master for the Port of Victoria and in June 1859 he was named Justice of the Peace. He died here in Victoria on January 5, 1882. He was 81. He is buried at Ross Bay Cemetery.

[3] Kilian Crawford, Author “Go Do Some Great Thing: The Black Pioneers of British Columbia” Commodore Books, 2008.

[4] Reverend Edward Cridge, from his diary Thursday, May 6, 1858. “On Sunday Apl. 25 the Commodore, Capt. Nagle, arrived with 400 or 500 Emigrants from San Francisco. There were also 35 men of colour from the same place of different trades and calling, chiefly intending to settle here. On Monday (Apl. 26) drinking tea at Mrs. Blinkhorn’s with my wife, she (Mrs. B) told us that on the preceding evening she was surprised at hearing the sounds of praise. They proceeded from the men of colour who had taken a large room at Laing’s the Carpenter; and they spent the Sabbath Evening in worshiping the word of God.”

[5] Archy Lee. His story is not fully known, however he is mentioned in Reverend Edward Cridge’s diary entry of Tuesday, May 25th 1858 [4] as one of the people that visited with Reverend Cridge when the Committee arrived. He initially found work as a porter. He is later mentioned in the Daily Colonist on February 25, 1862 “Snowballing and Fisticuffs. The article reports that a skirmish broke out when Archer Lee, whose arrest as a fugitive slave from Mississippi created a great excitement in San Francisco about four and a half years ago, believed a white man had thrown a snowball at him. A crowd of about 100 had gathered, but no arrests were made”. In 1864 it is noted “he follows the lucrative occupation of draying, has accumulated some property, and is much respected by the community”.[3] Lee is believed to have died here of illness circa 1873.